The Careful Scientist exercise requires following a small set of joint movement rules which dictate the ways a performer’s arms may move. As part of the rule set no movement that is happening on the one side of the body can happen at the same time on the other side of the body. Because the options are so discrete and constrained, the number of possible action sequences can be calculated. As we have discussed here previously, the movements are limited to:

- Upper Arm Pointing

- Shoulder Rotation

- Elbow Flexion

- Forearm Rotation

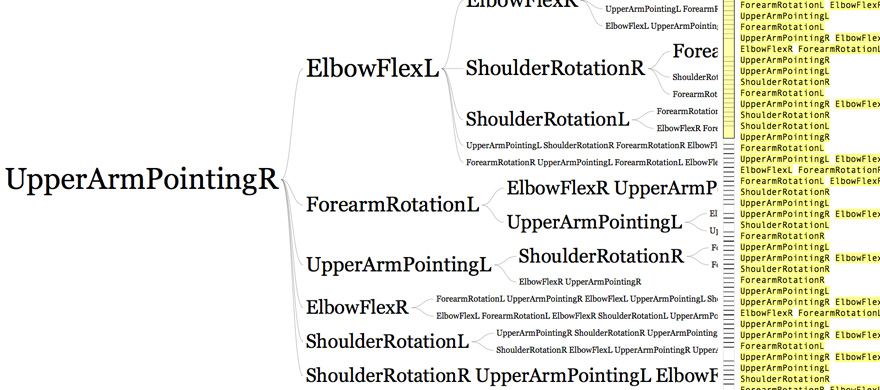

With a new action being chosen roughly every 1-3 seconds, there are millions of possible sequences for the first half minute of the exercise. Calculating the number of permutations was useful for giving a sense of the number of possibilities for this seemingly very constrained exercise. It also furthered discussion of choice-centric vs. action-centric perspectives of the exercise. Diagramming the options for the beginning sequence, and the possible choices that emerge quickly revealed the simple pattern that follows.

From an internal, experiential choice-centric perspective, I note that I begin by choosing a starting action to perform in one of my arms (“action 1”) followed by a starting action to perform with my other arm (“action 2”). I then begin moving by starting both action 1 and action 2 at the same time. From this perspective, I had 8 possibilities for my first choice. My selection then led to only 3 options for my second choice. There are 8*3=24 possibilities for this initial sequence of choices.

However, from an action-centric perspective, when I simultaneously begin performing my initial choices, “left Elbow Flex & right Forearm Rotation” is exactly the same activity as “right Forearm Rotation & left Elbow Flex”, regardless of the order in which I selected these two actions. From this perspective, there are (4*4)-4=12 initial combinations for how the arms can begin moving. (Four possible actions in each arm yields 16 possible combinations, minus the four “illegal” combinations where both arms are doing the same action.)

Left Right

1 2,3,4

2 1,3,4

3 1,2,4

4 1,2,3

After both arms begin moving, as long as you “change the actions in both arms at different times, so that the action in one arm continues while you change action in the other” (Thomas) then each additional change multiplies the permutation count by 4. This results from having four options at any time for the next action: the left arm could change to one of two other actions, or the right arm could change to one of two other actions. Neither arm is allowed to repeat their current action, and neither change to the action the other arm is currently doing.

action choice permutations

1 12 12

2 4 48

3 4 192

4 4 768

5 4 3072

6 4 12288

7 4 49152

8 4 196608

9 4 786432

10 4 3145728

For ‘n’ actions: P(n) = 3 * 4^n

While the above shows the action-centric perspective, the only change necessary to switch to the choice-centric perspective, is that actions 1 and 2 have 8 and 3 choices respectively. The equation changes to P(n) = 6 * 4^(n-1), for n>=2.

Next steps could involve determining how variants of the rules effect the number of options. For example, if you allow both arms to change their actions simultaneously, how does this change the number of permutations? I suspect this allows the arms to swap actions, potentially increasing ‘4’ options to ‘6’, but there are dependencies that require further consideration.

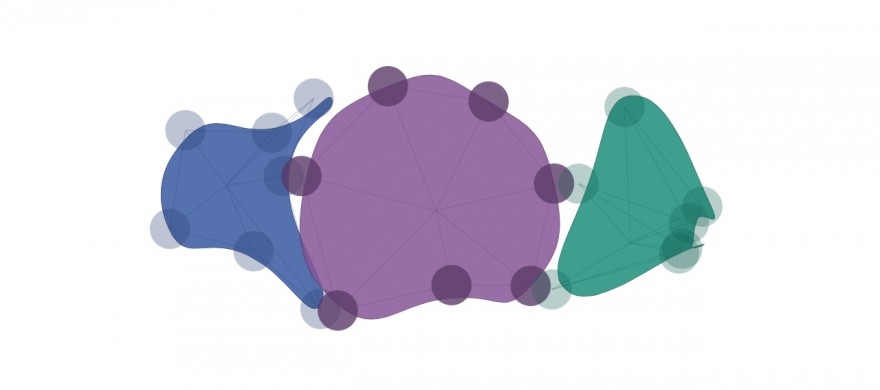

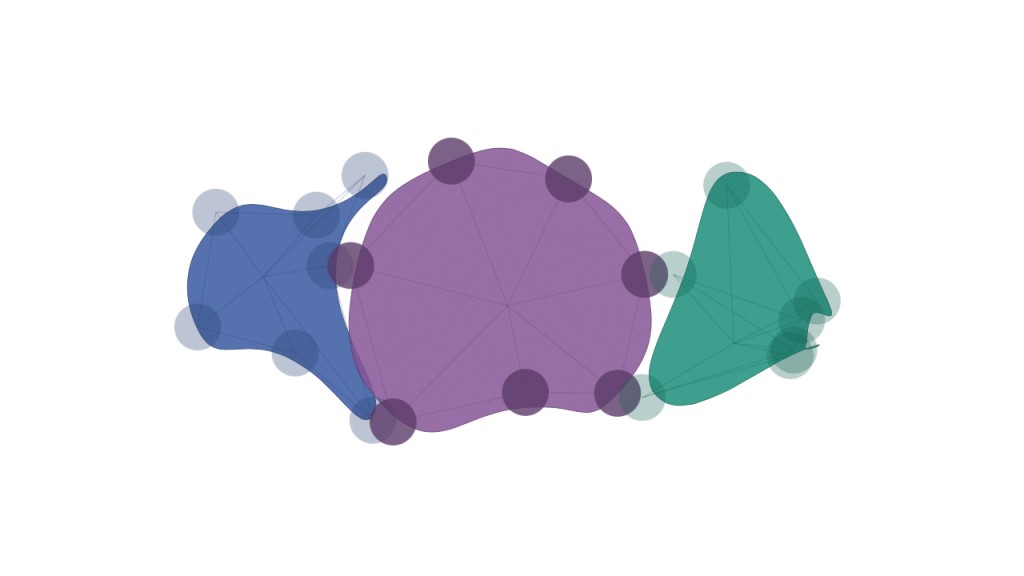

I wrote a script that counts actions, pairs of actions, and trios of actions for each (and both) arms. One of the next steps may be to generate some graphics to reveal patterns or lack of patterns in their action choices in pairs and trios.

And graduate research assistant J Eisenmann pointed out that there are some other ways to show the action ordering frequencies.

-Matthew Lewis, ACCAD Graphics Researcher