A Few Questions and Responses

Posted on November 27th, 2013

Meta Academy compilation of images

On Tuesday, I had the pleasure of talking with Nik Haffner, Marlon Barrios-Solano and their students at the Inter-University for Dance Berlin (HZT Berlin) about our TWO project and the upcoming Motion Bank launch in Frankfurt. The students talked about the connection between dance and technology and asked how I came to work in this field of research. It reminded me how little I think of all this as “technology” and how much I orient around the human collaboration aspects of our work. It is the relationship between computing ideas and choreographic ideas that so defines my research in the last couple of decades. And it is the engagement between the culture of art and the culture of science that has become our true methodological space. Interdisciplinary work is intercultural work.

Here are a few more of the questions from the students and my responses:

What is the TWO project? Is it two different scores for two artists?

The TWO project is ONE digital score focusing on the thinking body and dancing mind (a phrase I am borrowing with permission from the illustrious David Gere and his Introduction to Taken by Surprise, an excellent compilation of articles on dance improvisation). So it is one project. One Score. Two artists. In some writing I did for the project I recently explained it like this:

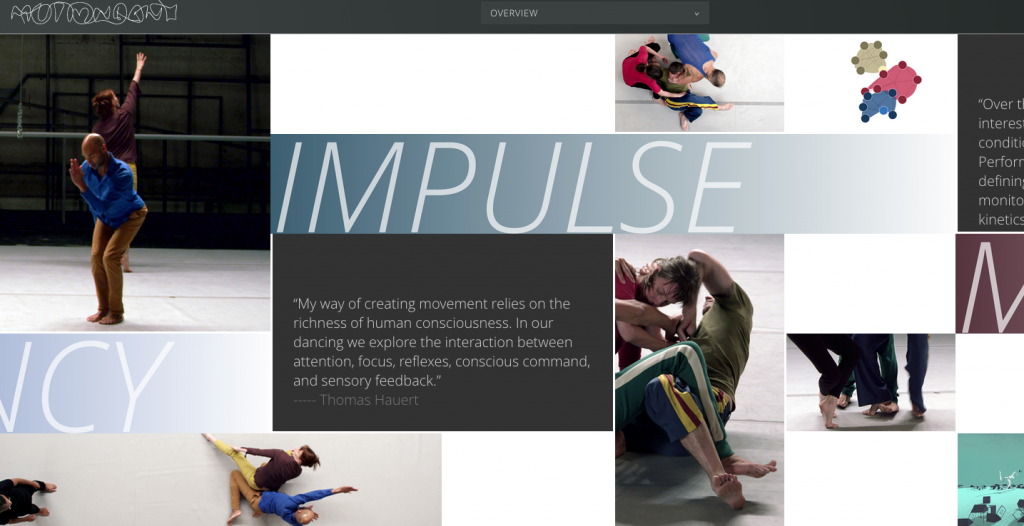

Our work begins and ends with two dance companies. Unrelated to each other. One from the US (the Bebe Miller Company) and one from Europe (Thomas Hauert’s Zoo Company). Both are currently choreographing improvisation for performance. And both are engaging directly with the nature of human consciousness. When we watch the dancers, we are watching them at work. We are witness to the concentration and forms of attention that they bring to the moment. And we are witness to their habits, tendencies, attention, impulses, and memories in action. In this project, we have selected two working strategies each from the two companies to shed light on and bring us into a direct encounter with what the dancing mind and the thinking body. In an early storyboard for the project I called it The Dance of Attention but that was actually too limiting.

How were the artists for Motion Bank chosen?

For our part it was very intuitive really. We wanted to start from a different place then we had started with Synchronous Objects. We decided to start from a choreographic phenomenon and then look into the processes of two different artists to see what insights their ways of working might shed on that phenomenon. We were looking for people we could enjoy working with who also had a relationship to deep process and had some small-scale works (2 or 3 dancers). Bebe Miller was a natural fit because she was engaged in a duet project with her company and we knew a lot about her working methods. We found Thomas Hauert’s work through our friends at Germany’s hidden gem, the PACT Zollverein Center for Choreographic Research. PACT helped support our work by funding a residency for me and Thomas to exchange ideas and everything just unfolded from there. I immediately appreciated Thomas’ sense of processes that generate movement and his interest in the cognitive challenges that improvisation can involve.

Did you make everything you planned to make? Will you share the data so other things can be made from your resources?

Deadlines always mean something gets cut and that’s certainly the case with us. At some point you have to “put the show on the stage and turn on the lights.” We hope to add a few more animations and graphs in the coming months but what is online is a full representation of the project. We would love to share the data from this project and Synchronous Objects any time there is interest. Motion Bank is a kind of open source initiative. When Forsythe dreamed it up he really wanted it to act as a catalyst for other artists to explore digital scores and traces of choreographic thinking and to make tools that can be used by all kinds of artists for even more projects. I think the Piecemaker tool they created is super useful and the publishing system for the scores. And I hope the ideas are too.

Can you share more about the scores and ideas you selected from Bebe Miller and Thomas Hauert to discuss perception/cognition?

While the two dance companies we are focusing on are both interested in the forms of perception and consciousness accessed and enacted in improvisation, they explore those questions with very different strategies. We focus on four of those strategies in the sets you’ll see in Motion Bank at the launch on Thursday. The project is divided into four sets with the following titles: Habit, Tendency, Impulse, and Memory. I look forward to having it out in the world and knowing what ideas, questions, critiques, interests it brings.

—Norah

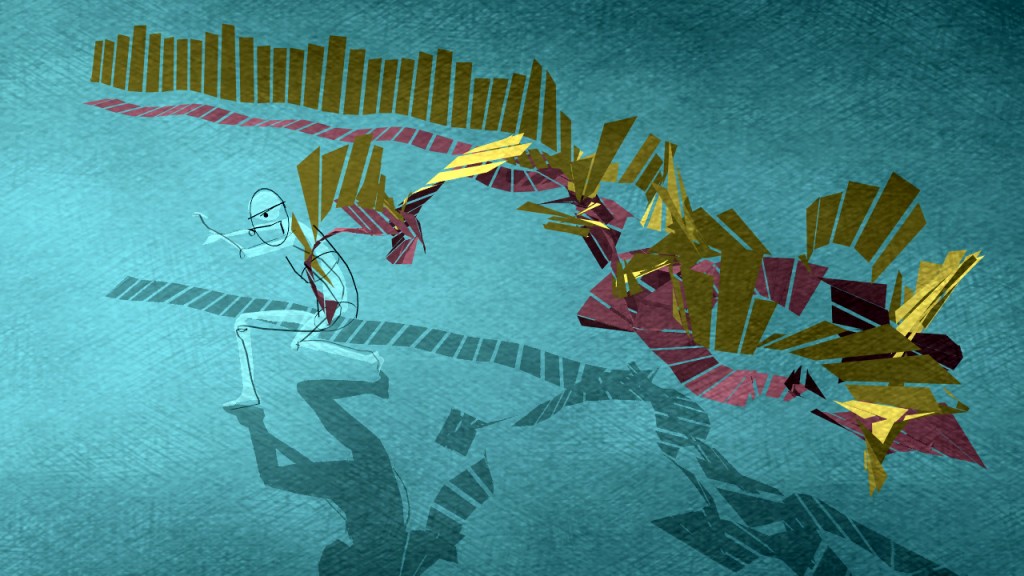

Screen shot from our Motion Bank project TWO that will be online November 28th

Tagged: Attention, cognition, consciousness, HZT, launch, Marlon Barios-Solano, Nik Haffner, perception, scores, student